(An Excerpt From Exhilarating Prose: A Writer’s Manual

A work in progress by Barry Healey & Cordelia Strube)

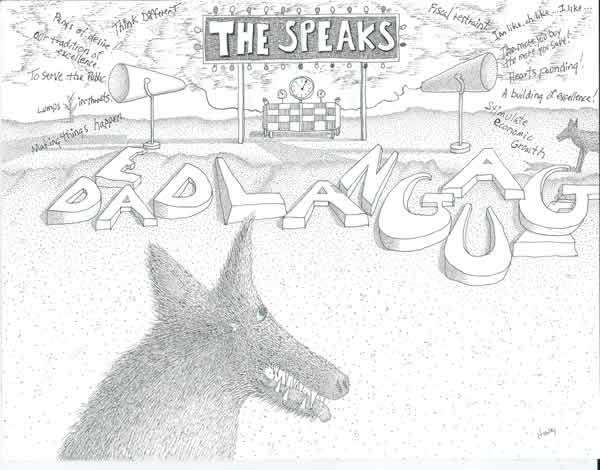

DEAD LANGUAGE – THE SPEAKS

What is it?

Dead language is language that is… well, dead. Like the Monty Python parrot, it is deceased, expired, no longer of the living. It litters the cultural landscape. It’s leaden, repetitive and un-arousing—prose unable to transport the reader anywhere.

You cannot write sparkling prose with dead language. The writer needs to metaphorically jab the reader in the brain with a sharp stick; to replace mirthless, incoherent, disingenuous words and phrases with lucid and startling ones. The writing must be sparse, sharp and vibrant to stimulate the reader’s imagination. Each word, phrase or sentence must be tested before being deployed—effective prose is uncluttered, and contains no unnecessary, misleading, bland or deceptive words which might smother imagery or meaning.

Dead language is made up of ‘The Speaks’—ad-speak, media-speak, techno-speak, medical-speak, valley-girl-speak, art-speak, sports-speak, corporate-speak, government-speak, and a hundred other speaks—clusters of clichéd words and phrases, replicating the same oral and written syntax, effectively blocking the communication of forceful and original ideas.

Advertising is the rattling of a stick inside a swill bucket.

~George Orwell

Ad-speak—like “Doublethink” in Orwell’s 1984—is now wholly incomprehensible (e.g. our local jazz radio station advertises “This commercial free Sunday is brought to you by…”). Everywhere in the media you find, “The more you buy, the more you save!” One imagines chimps bouncing on chairs in ad agency cubicles, pounding their keyboards and chanting, “the more you save, the more you buy, the more you buy, the more you save”.

Ad agencies refer to their efforts as the ‘Art of Persuasion’ (not the ‘Art of Deception’?). Ad-speak practitioners seem particularly adept in the use of dead language, describing the merchandise or services they’ve been retained to hawk in the same clichéd superlatives, undoubtedly because the items being peddled have no intrinsic or exceptional value (i.e. selling the “sizzle” and not the steak).

Sharp, clear prose is not hesitant in stating what it’s about, unlike most ad campaigns which are built around vague, suggestive slogans not intended to be interrogated, but cry out to be questioned:

“It’s good to talk” (what about listening, British Telecom?);

“Things go better with Coke” (diabetes, for example?);

“Fox News – Fair and balanced.“ (fair to whom, Rupert?);

“Doctors recommend Phillip Morris” (dead doctors?);

“You can be sure of Shell” (sure of spills?)

“An army of one” (are you counting on both hands, Pentagon?);

“Think Different” (shouldn’t you go first, Apple?);

“Rediscover delicious harmony” (delicious or nutritious, McDonalds?);

Ad-speak is designed to seduce and reassure, employing vague non sequiturs presented in rhythmic, inane phrases. Ikea seems to stand alone with its plain and witty, “Screw yourself”.

Business-speak (a division of ad-speak?), possibly the greatest purveyor of dead language (i.e. course descriptions in a business school calendar), utilizes vacant and tiresome phrases such as “our tradition of excellence in…” and “forward thinking attitudes of our staff”, along with “to serve the public”, to dupe the consumer into believing that they are receiving value for money, and to obscure questionable business practices. Ask yourself: would any company, manufacturing a viable, useful and lasting product, or ably providing a needed service, require the use of dead language to promote its goods or services—if those goods and services were highly regarded?

“I grew up on a farm. I know what it means to restore the land,” says Garrett, a youthful “environmental coordinator” for ConocoPhillips, standing in a forest in a (full-page) magazine ad. Garrett is being disingenuous. His phlegmatic statement is intended to imply that the oil industry’s Tar Sands operations, a 40 metre deep gouge the size of the state of Delaware in northern Alberta’s Boreal forest—considered by most ecologists and scientists the most environmentally destructive project on the planet—is being (or will be) magically restored by the oil industry; but of course he doesn’t say how. Garrett’s knowing “what it means to restore the land” is meaningless ad-speak. The oil industry has no idea of how to bring the Boreal Forest back to life (unless it knows something the Gaia doesn’t).

In the same oil industry-financed campaign, another full page ad shows Megan, a young biologist in a wetland, employed by Devon Energy, telling us that she is “monitoring the plants, soil and animals… We know,” she says, “what was here before, what’s here now, and what we need to do before we leave.” What, Megan, what?

Millions of dollars are expended by ‘resource’ (fossil fuel and mining) industries each year to produce reams of dead language to mask their destruction of our once pristine landscape from public view; and they presume that, by presenting Garrett and Megan’s handsome, young, educated presence, and their Pollyannaesque comments, they will quell public apprehension. Their rhetoric—as murky as a tailings pond—attempts to assure us that the rapacious extraction practices of the resource companies have little impact on our landscape.

“Water (the campaign further informs us) is an important part of oil and gas production, and as Canada’s oil and gas industry grows, so does demand on Canadian water resources.” This sentence, cowering on the page, hopes to demonstrate that the oil industry is concerned about the preservation of fresh water; but if so, why are they poisoning so much of it? And why aren’t Garrett and Megan informing their lubricious bosses that polluting millions of gallons of fresh water and decimating our Boreal forests for profit are, ultimately, acts of genocide?

Corporate-speak suggests action while avoiding it, as in “our team will explore specific environmental goals”. This statement suggests much more than the sum of its parts. The word “explore”—like Megan’s use of the word “monitor”—paired with the word “specific” raises expectations that a definite action is being taken; but actually it’s describing a non-action involving no commitment—nothing is rectified, proscribed or initiated, nor is the destruction of the environment halted.

“Our team will explore specific environmental goals” implies that the destruction (by the writer) of our natural world is being dealt with; but will all this “exploring” (and “monitoring”) lead to solutions? Unlikely. The team “explores” only; the word “specific” is used to suggest focus—but of what? More probably, additional consultants will be retained to “explore”, “monitor”, and compile further reports in dead language.

Corporate-speak is similar to government-speak—both using technology and dead language to nullify access. Do you remember the last time you attempted to contact a large corporation or government agency? Or how long it took, using voicemail or the internet, to obtain the information or service you needed?

Dead language is also extant in the medical, legal, and building professions. Architects, for example, when preparing design proposals rely on abstract phrases to convey a tone of proficiency, but what do the phrases “flexible activity rooms”, “needs assessment analysis” and “presentation forums” actually mean? Might not a “flexible activity room” be a place of deviant behaviour? And what would a “presentation forum” look like? How many humans—or Martians—might it hold? Is it likely to contain an “organic simplicity” (as Frank Lloyd Wright hoped)?

And what would distinguish a “building of excellence” from one that is not excellent? What shape would it take? A triangle, a stilted box, or—even stranger—an inexplicable eruption of jagged, irregular-shaped pyramids jutting out randomly at all angles, capriciously fixed to a once elegant, now sadly disfigured, historical edifice? Could there be a symbiotic connection between the many misshapen structures that litter our contemporary landscape and architects’ design proposals replete with dead prose? Is there a link between vibrant language and graceful structures?

“The problem with so much of today’s literature is the clumsiness of its artifice—the conspicuous disparity between what writers are aiming for and what they actually achieve. Theirs is a remarkably crude form of affectation: a prose so repetitive, so elementary in its syntax, and so numbing in its overuse of wordplay that it often demands less concentration than the average “genre” novel. Even today’s obscurity is easy, the sort of gibberish that stops all thought dead in its tracks.”

B.R. Myers, A Reader’s Manifesto

In fiction and non-fiction, the rampant use of clichés—surely a keen example of language that has succumbed—is relentless: “hearts lurching”, “hearts pounding or pounding hearts”, “racing minds and hearts”, “leaping / sinking / stopping hearts and stomachs”, “breaking into a smile”, “pangs of (anything)”, “seizing, or lumps in, throats or stomachs” submerge the reader into a quagmire of meaningless jargon.

The words “smile” and “laugh” (as noun and verb) are repeated endlessly. What do writers of the cliché imagine—that readers will find comfort in familiar words and phrases rendered hue less by overuse? Do they fear that new words and forceful expressions might intimidate or confuse the reader? Or, are they simply unable to visualize new utterances and syntax to express their ideas?

Dead language kills thought, quashing original ideas. Stories need to be told with penetrating simplicity. The eager reader would rather not face acres of turgid prose; but the canny writer must not assume that the reader is dull-witted. A Canadian ‘literary’ organization which pays authors to write novels, cautions them to avoid odd words (i.e. “muted”) that the organization presumes might baffle the reader. This covert form of censorship, reminiscent of Orwell’s ”Newspeak” in 1984, demonstrates ignorance of the process. With any well-written work, the reader will not necessarily comprehend every single word, but if the story, and the writing, are engaging he or she will by-pass words they don’t know—which they may have come across for the first time, and will come across again—eventually surmising their meaning [see the John Holt anecdote in The Stillness of Reading chapter].

Isn’t this how enlightened citizens are formed, acquiring a large working vocabulary and extensive knowledge through indiscriminate reading—a process formerly known as a ‘liberal education’? Reading is an inoculation against dead language. Done with abandon, it can introduce readers to unique word possibilities, expand the acquisition of new ideas, and—through eloquent, pertinent stories—provide a refuge from life’s mental vagaries.

“He that reads and grows no wiser seldom suspects his own deficiency, but complains of hard words and obscure sentences, and asks why books are written which cannot be understood.”

Samuel Johnson, The Idler

Given that dead language—in its paper state—eradicates thousands of hectares of trees each year, shouldn’t we abolish it? Could we not persuade our political leaders to legislate its demise? Or, might we risk exposing ourselves to the following response:

“There is no question that the issue of dead language is critical, and needs to be addressed at this time. And so, with our government committed to decisive action in staying the course in this era of global financial restraint; yet continuing to build a diverse and prosperous Nation, we will be pursuing an active role in considering possible legislation which, when enacted, will—with clear deadlines and decisions, and fiscal discipline—create not only wholesome prose and speech, but stimulate economic growth, protect our environment, enhance native cultures and support the valiant men and women who serve in our armed forces; enabling all Canadians to be themselves.”

Ultimately, it will be up to the writer to banish the ‘speaks’—to hone every thought to its essence with clear, plucky sentences so that, on the horizon, set off against a violet sky, we will stand breathless, gaping at a line of sharp, vibrant prose.